There’s a common pattern where some men seem to have a complete inability to understand women when they speak. As far back as the 1970s, this kind of interaction has been illustrated with humor:

The term mansplaining was coined more recently, sparked by Rebecca Solnit’s 2008 essay Men Explain Things to Me. Solnit’s stories present a different perspective from the prevailing narrative that women lack confidence to speak up: perhaps the lack of confidence is not in ourselves but rather in our audience. One must be an authoritative expert on a subject with footnoted documentation before having the right to an opinion, and even then, we may be inaccurately criticized or simply ignored.

It was a few years ago when I realized that I had accepted the status quo. I was on a conference call with two male colleagues. I was caught up in the discussion and hadn’t noticed that I had initially put forth an idea that was then attributed to my other male colleague. Instead of tacitly accepting credit for my idea, he promptly said “I agree, that was a great idea that Sarah had.” A simple correction, said kindly with an edge of humor, honored my contribution while gently chiding our colleague. Most men have the capacity to listen to the words I say and follow the thread of the idea, and some realize that correct attribution is a simple respect that fosters effective collaboration.

A couple of weeks ago, Jen-Mei Wu, Judy Tuan and I were talking about code and sharing stories of our lives. With dark humor, I noted that for some men, it seems that my voice is unintelligible. I know they hear me, since they typically wait till I finish speaking before repeating themselves verbatim as if I had not spoken or asking a less knowledgeable man to explain in more detail. I joked that I needed a personal translator, a man who would attend meetings with me and repeat what I say for some of my colleagues who can’t seem to understand my words.

We wondered if this behavior might stem from the need to compensate for a cognitive disability where some men can hear female voices, yet struggle to discern meaning from sound. Without self-awareness of their own affliction, when they hear the garbled syllables, they assume the woman is not speaking clearly, and so they feel compelled to repeat their understanding of the words. Tech companies might identify men who are thus impaired and offer mansplaining-as-a-service as a benefit to accommodate this peculiar affliction.

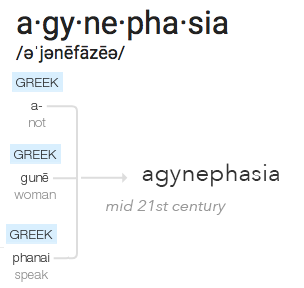

I sought a word to describe this new insight about a potential root cause, perhaps a previously unknown form of aphasia where some men cannot cognitively process words when they are spoken by women. It seems important to separate the community service where a man will amplify a women’s ideas by repeating key points with attribution, as distinct from the bizarre echolalia commonly known as mansplaining which may be a further symptom of this affliction.

In reading further on this subject, I discovered some research indicating that there might be a physiological basis for this syndrome. Further study may be needed. Independent of the neurological processes involved, I suggest the word agynephasia to describe this phenomenon.

I urge men to support your colleagues who may be unaware of their disability. Until the tech companies start routine testing for this affliction and providing trained assistants, you can help by learning about the expertise of your colleagues and dinner guests, regardless of their race or gender, correctly attributing ideas, and helping to redirect the discussion if needed.